Eric Gill: The Troublesome Genius

SHARE

It is a common belief that a brilliant artist is not subject to the norms that limit us, ordinary mortals. He, it seems, is simply allowed more. Crossing subsequent barriers, experimenting with one's own experiences, sexuality, as long as it then transforms into "high" art, is apparently allowed and often arouses the public's jealous curiosity rather than its indignation. There is, however, an exception to this seemingly inviolable rule, and it is an extraordinary one in every respect - Eric Gill.

Sculptor and typographer

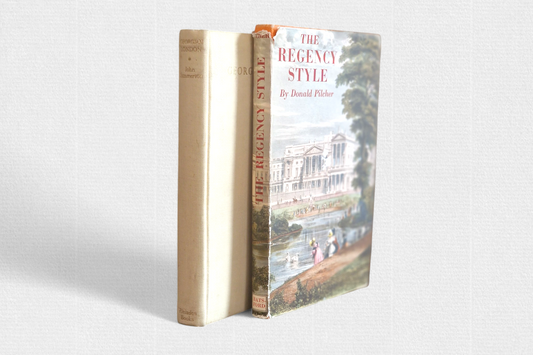

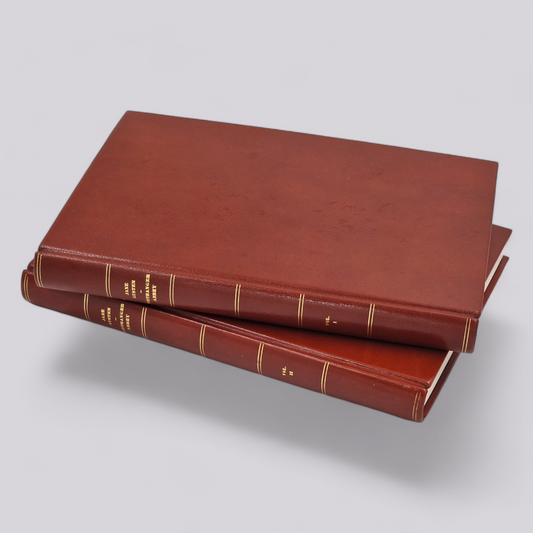

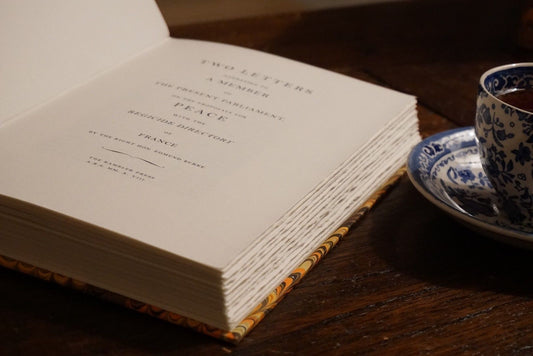

Born in 1888, Eric Gill was undoubtedly one of the most important British artists of the first half of the 20th century. His work, like many of his contemporaries, has not been covered by the dust of museum halls and warehouses. Gill's sculptures still arouse admiration, the fonts he cut (Joanna and Perpetua) captivate with their elegance, and books published by Golden Cockerel Press, whose form Gill took care of, are still sought after by bibliophiles. Suffice it to say that in 2016 the first Polish edition of his Typography , originally published in 1931, was published. His characteristic outfit, emphasizing the artist's aversion to bourgeois uniformity - a long smock girded at the hips (an adaptation of the then completely anachronistic Welsh folk costume called "smock"), a hat, woollen socks and no trousers - became not only an individual trademark, but also to some extent a symbol of the artist as such in the past century.

Gill initially intended to become an architect, but dropped out in 1903 and took up sculpture (at Westminster Technical Institute) and calligraphy at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, where he studied under the famous Edward Johnson (who designed the London Underground logo, among other things). In 1912, he achieved his first great success with the sculpture Mother and Child. Two years later, Gill created the Stations of the Cross, intended for the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Westminster, built at the turn of the 20th century. However, he achieved real fame only after the First World War. He created many monuments commemorating British soldiers who died on the fronts of the Great War. The 1920s and 1930s were a period of great triumphs for Gill as a sculptor. His works were used on the building that housed the BBC, the London Transport Authority, and the Geneva headquarters of the League of Nations. In fact, it is difficult to imagine European sculpture of the interwar period without the works of Eric Gill.

Sculpture, however, did not exhaust his artistic passion. In 1914, he met Stanley Morison, one of the most outstanding British typographers and researchers of the history of printing. Under his influence, Gill began to be interested in designing fonts and graphic symbols. In 1929, Perpetua was created, created on behalf of the Monotype Corporation, a tycoon involved in the production of printing equipment. Two years later, the Gills Sans font was created, which is still used in the graphic symbols of the popular English series of Penguin books, the BBC and British railways.

Catholic and socialist

Gill was far from devoting himself solely to art. Like many artists of the past century, he had strong political convictions, which he expressed publicly. Already in the war memorial created for the University of Leeds, instead of the usual military symbolism, Gill reached for the biblical image of Christ driving the merchants out of the temple. The sculptor's work aroused much controversy at the time, but it was an expression of his strongly left-wing belief that war was the work of merchants and capitalists.

The artist did not hide the fact that he considered himself a socialist. In Typography he wrote: "Time and place must be taken into account when discussing each of the human affairs, especially in an era as terrifying as the 20th century. It is not our business to dwell on its perversions, but they must at least be described, although, as is often the case, it is easier to say what they are not than what they are. They are not a deviation from the norm caused by the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few and the poverty of the many; such deviations in any direction do not have to destroy or disturb the basic humanity of our lives. Nor is it about a free minority remaining in opposition to an enslaved or oppressed majority. A state organized in this way may be ethically evil or good, but neither the free nor the slaves are necessarily condemned to a life contrary to nature. The monstrosity that makes our age unnatural is the deliberate and unwavering determination to render both man’s working time and what he produces in it mechanically perfect, and at the same time to relegate everything that is human by nature to the realm of leisure, when not at work.” The artist must be given credit for living in accordance with his convictions. Despite his growing fame, he kept to the margins of the “big” world, living in the deep provinces, where – as his biographer, Fionna MacCarthy, writes – “…he returned to what he considered the “normal life” of his ancestors, before the cult of city life and its cheap goods.” Apart from art, the artist’s attention was drawn to his garden, his animals, and the “ancient art of mowing.” Gill’s family formed a kind of Catholic commune, where they lived in forced simplicity, “…gathering around the kitchen table, expressing their satisfaction in a meal of freshly slaughtered pig and home-baked bread.” The artist's adolescent daughters grew up deprived of wider contact with peers, taught only by their parents, and their time was divided between studies, work on the family farm, and prayer.

As a young man he was a member of the Fabian Society, later in the interwar period he officially supported the left, fought fascists and clearly supported the republicans during the Spanish Civil War. He remained faithful to his declared pacifism until the end of his life. However, when he died in November 1940, he saw Europe sinking once again into the depths of bloody madness.

Gill combined his socialist beliefs with a deep religious faith. In 1913 he became a Catholic, taking his wife (who took the name Mary) with him. As MacCarthy noted, "his native Anglican church was too shallow for someone torn by such spiritual and intellectual desires." Gill himself believed that "there is no mysticism without asceticism."

Perversion as a principle

It is no wonder that Gill was a very popular figure among English Catholics in the interwar period. This was not changed by his numerous erotic drawings, often using figures of saints, shown in unambiguous, sexual poses. Their iconoclastic power was undoubtedly weakened by the fact that they were free from any vulgarity. On the other hand, the combination of corporeality and spirituality makes them incredibly moving. We are undoubtedly dealing with art, not primitive pornography. One of the artist's early works, depicting a copulating couple, was bought for his office by John Maynard Keynes himself. When asked how his employees reacted to it, he replied: "They are trained not to believe their own eyes". Nevertheless, the artist's works, sometimes very explicitly depicting genitals, caused not only a stir but also gossip and suspicions related to his sexual life.

Despite this, Gill's reputation remained intact for many years. The first biographies that appeared in the 1960s were very discreet in describing the artist's privacy. Just in case, the family entrusted his very meticulously kept diaries (40 volumes!) to the care of an American university and restricted access to them. The scandal broke out only in 1989, when Fiona MacCarthy's work Eric Gill: A Lower's Quest for Art and God was published. The author managed to get access to the artist's diaries, and what she found in them caused a real stir. She found in them a detailed record not only of numerous marital infidelities (one of Gill's lovers was the outstanding American typographer Beatrice Warde, who did a lot to popularize his typefaces overseas), but also of pedophilia and incest. Gill also diligently noted his erotic "experiments," such as the intercourse he had with his dog. Sex became a real obsession for the artist, without it he probably could not live or create. His diaries repeatedly recur with his admiration for "the most precious ornament of a man" and descriptions of his reactions to various situations.

When MacCarthy's book was published, it caused a real scandal. The author was accused of flaunting vulgarity and not taking into account that one of the artist's daughters, Petra Tegetmeier, was still alive (she died at a ripe old age in 1999). However, no one had any doubts that Gill would find himself in prison today, sentenced to a long sentence for sex crimes. The BBC asked directly, "Can you celebrate art created by a paedophile?" A group of awakened Catholics demanded that the artist's Stations of the Cross be removed from Westminster Cathedral. As one activist claimed, "[Gill] abused his servants, prostitutes, animals, had sex with everything that moved," so how can you pray to his work? Fortunately, Bishop George Stack unequivocally rejected all such suggestions, stating "that taking [the Stations of the Cross] down is not being considered." A work of art has its own rules. Once created, it takes on a life of its own." Similarly, the BBC refused to remove Gill's bas-relief from the front of its headquarters.

And indeed, the scandalous revelations about the artist's private life have only increased interest in his works. Nothing can take away his well-deserved place in the pantheon of the most outstanding artists of the 20th century.

But what can one think when one sees Gill’s female nudes and knows that his teenage daughters posed for them? Graham Greene, a great English writer of the last century and a deeply religious man, wrote about Gill with dislike and barely concealed disgust, considering him a hypocrite and essentially a poor artist. One may disagree with Greene’s opinion, but MacCarthy is probably right when he writes: “no one who knew him [Gill] well could like him.”

The text was originally published in the monthly Historia bez Censory in December 2016.

Above: Eric Gill, Votes for Women , 1911