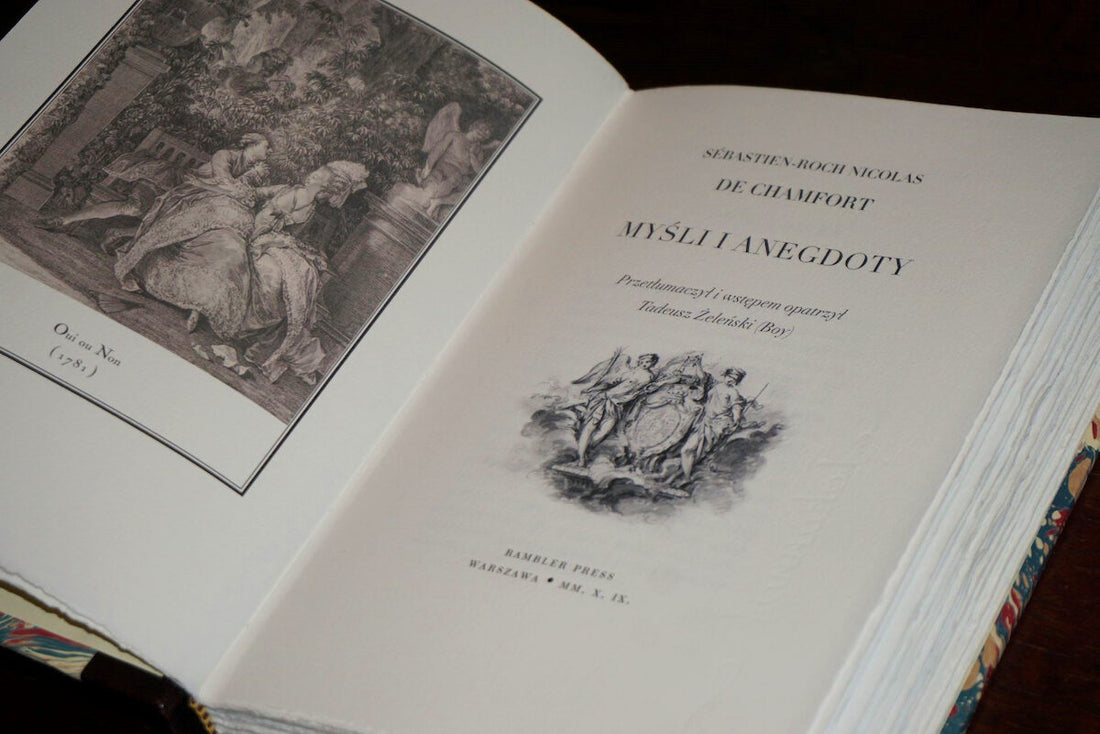

Chamfort seen differently

SHARE

It's hard to hide that Chamfort is one of the funniest books in our publishing house's output to date. First of all, because of its extraordinary sense of humor. It was not without reason that Boy wrote about it that "one could almost say that if everything from that end of the 18th century were lost, it would be possible to recreate it from these anecdotes of Chamfort, as aptly chosen as they are brilliantly edited. The king, the court, the clergy, the high society, women, finances, politics, intrigues, favors - all interwoven with the same pessimistic philosophy, but less tedious here, because more nourished by fact and brightened by wit. The end of an era, a dying world - and dying justly! This volume of anecdotes has become a document; this small volume has made Chamfort the most frequently quoted of authors and given him real immortality."

It's just that Chamfort's contemporaries remembered him a bit differently. It's worth remembering that too.

Chamfort

Among all the men of letters who visited me there was one man whom I could not stand, as if I had a premonition of what the past would bring me: it was Chamfort. However, I received him very often out of courtesy towards certain of my friends, and especially towards M. de Vaudreuil, whose sympathy this man had won, all the more so because he was unhappy. He showed much intelligence in conversation, but he was sarcastic and full of bile, which had no charm for me, and besides, his cynicism and slovenliness irritated me very much.

His real name was Nicolas; he had changed it at the advice of M. de Vaudreuil, who was anxious to introduce him into good society, and even, if possible, to the Court. M. de Vaudreuil lodged him very comfortably in his own house, and as he was almost always at Versailles, he had him board with Chamfort and such persons as Chamfort wished to invite during his absence. In a word, he treated him as a brother; and this man, when his revolutionary friends reproached him afterwards for living in the house of a nobleman, would reply basely: "What do you want? I was Plato at the court of the tyrant Denys." I ask what kind of tyrant was M. de Vaudreuil. But what kind of Plato was Chamfort too!

His close intimacy with Mirabeau, and especially his envy of the powerful, which had always consumed his soul, soon made him a mad supporter of the Revolution. It is known that he proved one of the most bitter enemies of the throne and the nobility, forgetting, or rather remembering, that he had been court secretary to the Prince de Condé and Madame Élisabeth, both of whom showered him with favours. Contrary to the proverb which maintains that wolves do not devour one another, Chamfort was thrown into prison by the men to whom he had served so well both by his speeches and by his pen, and when he was about to be arrested again after his previous release, he cut his own throat with his own razor.

Louise-Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Memories , translated by Irena Dewitz, Warsaw 1977